Squats and Romanian deadlifts (RDLs) are excellent strength movements, but they also load the lumbar spine heavily. When a lifter develops low back pain during or after these lifts, it does not automatically mean the same thing for everyone. Sometimes the issue is a temporary irritation; other times it reflects a deeper mechanical problem that needs a proper exam.

This article explains common movement-related reasons squats and RDLs can trigger low back symptoms. For a full diagnosis-first breakdown of low back pain, disc bulges, and sciatica—including how we evaluate these problems and how treatment is decided—see:

This post is educational and not a diagnosis. If symptoms persist or travel into the leg, evaluation matters.

Why These Lifts Stress the Low Back More Than Most Exercises

Both squats and RDLs increase spinal loading because they require the trunk to resist forward flexion under weight. Even with excellent form, the low back and hips are absorbing significant force. Small changes in fatigue, mobility, or bracing strategy can shift that load toward tissues that are already irritated.

Common triggers include:

-

Increased training volume or intensity (even without “bad form”)

-

Training through fatigue (bracing quality drops)

-

Reduced hip mobility leading to more lumbar motion

-

Returning too quickly after a flare-up

1) Lumbar Flexion Under Load (A Common Mechanism)

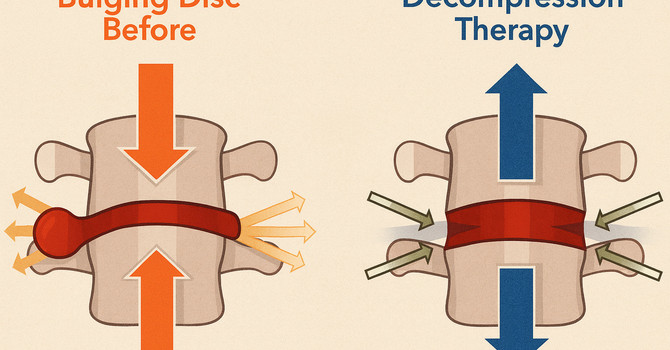

When the lumbar spine rounds under load—sometimes called “butt wink” in squats or spinal flexion drift in RDLs—disc pressure and posterior tissue strain can rise. Some lifters tolerate this well; others don’t, especially when training volume increases.

This does not mean every lifter with pain has a disc problem. It simply means lumbar flexion under load is a common mechanical irritant and often worth addressing.

If your symptoms include pain that spreads into the hip or leg, or persistent numbness/tingling, see the broader overview here:

Disc Bulge

2) Bracing and Intra-Abdominal Pressure Failure

A strong brace helps distribute load across the trunk and reduce shear stress on the lumbar segments. When bracing fades—often late in a set, near max effort, or during higher rep work—the spine may absorb more stress.

Signs bracing may be an issue:

-

Pain appears late in sets

-

Pain spikes on the ascent from the hole in squats

-

Pain shows up during the “hinge transition” in RDLs

3) Hip Mobility Limits That Force the Low Back to Compensate

If hip flexion (and hip internal rotation) is limited, the body often borrows motion from the lumbar spine. That can turn what should be a hip-dominant hinge into a lumbar-dominant pattern—especially in RDLs.

Common signs:

-

You can’t reach mid-shin without rounding

-

Tight hamstrings are felt more in the low back than the legs

-

You feel “stuck” at a certain depth, then suddenly lose position

4) Irritated Facet Joints or Local Segmental Inflammation

Not all lifting-related pain is disc-driven. Some lifters develop localized low back pain that feels:

-

Achy

-

Sharp with extension

-

Worse after standing or walking post-workout

That pattern can align with irritation of the posterior spinal joints or surrounding tissues—again, something that requires exam context.

For diagnosis-first evaluation logic and treatment decision-making, reference:

Low Back Pain

5) When Symptoms Start Traveling Into the Leg

If symptoms move beyond the back into the buttock, thigh, calf, or foot—or you notice numbness/tingling/weakness—nerve irritation becomes a consideration. That doesn’t automatically equal “sciatica,” but it does raise the importance of a focused neurological exam.

Red-flag escalation: progressive weakness, worsening numbness, balance/coordination changes, or rapidly worsening symptoms should be evaluated promptly.

4) “What You Can Do Now”

If squats or RDLs are triggering symptoms, a reasonable first step is to reduce spinal irritation while maintaining training.

Common short-term modifications include:

-

Reduce load and total volume temporarily

-

Shorten range of motion to a pain-free depth

-

Emphasize bracing and tempo control

-

Swap to variants that lower lumbar demand (e.g., goblet squat, split squat, trap bar deadlift depending on tolerance)

If symptoms persist beyond a short flare window—or the pain begins traveling into the leg—an exam helps determine whether the pain is primarily mechanical, disc-related, nerve-related, or a combination.

5) Key Takeaway

Squats and RDLs can trigger low back pain for multiple reasons—often related to how the spine and hips share load under fatigue. This article covers common mechanisms, but a diagnosis should be based on history + exam (and imaging when indicated), not on symptoms or a single lift.

For full condition-level overviews (diagnosis-first), visit:

Dr. Ike Woodroof

Contact Me